How to Survive Bat “Attacks”

Before I start let me be upfront – bat’s don’t “attack” like a bear might attack you. Unfortunately, people still think they do. At the same time, bats can kill you. Let me explain how to both be safe and avoid the many ways you could die from interactions with bats.

If you think bats are out to get you, then you’ve probably been watching far too many vampire films. Walking into a bat cave that creates a giant swarm of bats just isn’t going to get you attacked. That’s not how their hunting behavior works. Like most wildlife, bats are basically uninterested in interacting with humans. We, on the other hand, have extremely important reasons to fully study and understand bats – for our sake and theirs. The variety of issues that can occur from direct and indirect contact with bats threaten human lives and bat populations. At the same time, we depend on each other. Safely sharing the planet with bats is a tricky, delicate balance of high importance. So first let’s dive into the basics.

Bat Basics

Roughly 1,200 different species of bats inhabit our planet. That means one out of every five mammal species is a bat! Yet how often do you recall running into one? Probably not many. Maybe you’ve caught a glimpse of them flying through your vision on a night out under the stars or swiping mosquitoes high above you at dusk, but I’m guessing not much more. Most of that is because they come out mainly at night and are exceptionally good at flying around unnoticed.

Bats range in size from the size of your thumb to huge, winged flying foxes with wing-spans of almost 6 feet!

Most bats eat insects or fruit. These two diets give bats a crucial role in our ecosystem. They eat a stunning amount and variety of insect pests. That means they save us serious money by keeping many pests from destroying the nation’s crops. A group of scientists at Boston University calculated American farmers save anywhere from 3.7 to 54 billion a year in essential pesticide use simply because of these winged mammals!

In addition to eating insects that could harm crops, bats are extremely important as pollinators. They help pollinate night blooming flowers and are responsible for pollinating over 300 types of fruit. Fruits like the dragonfruit and those from the famous saguaro cactus depend solely on bats to spread and make fruit – no other animals can pollinate them!

Other bats feed on fish, frogs, lizards and even other bats! Amazingly many of these bats are super-specialized to feed on individual animal groups like this.

Simply put, bats are awesome and we need them. If you have a fear that bats will go out of their way to harm you, I’m guessing it comes from the way they are portrayed in film and television – like Dracula, movies where the vampires sparkle – and even the scene in the 80s classic The Goonies where Martha Plimpton is screaming about rabies as bats fly around the kids in a cave. Those are, of course, all fiction and not rooted totally in science fact… but it turns out that the myth of vampires does stem from a little bit of reality.

First of all, there are a few bats (the vampire bats) that drink blood. This propensity for the life-giving force of other’s blood is known as hematophagy. It’s also a fun word to use next time you’re at a party!

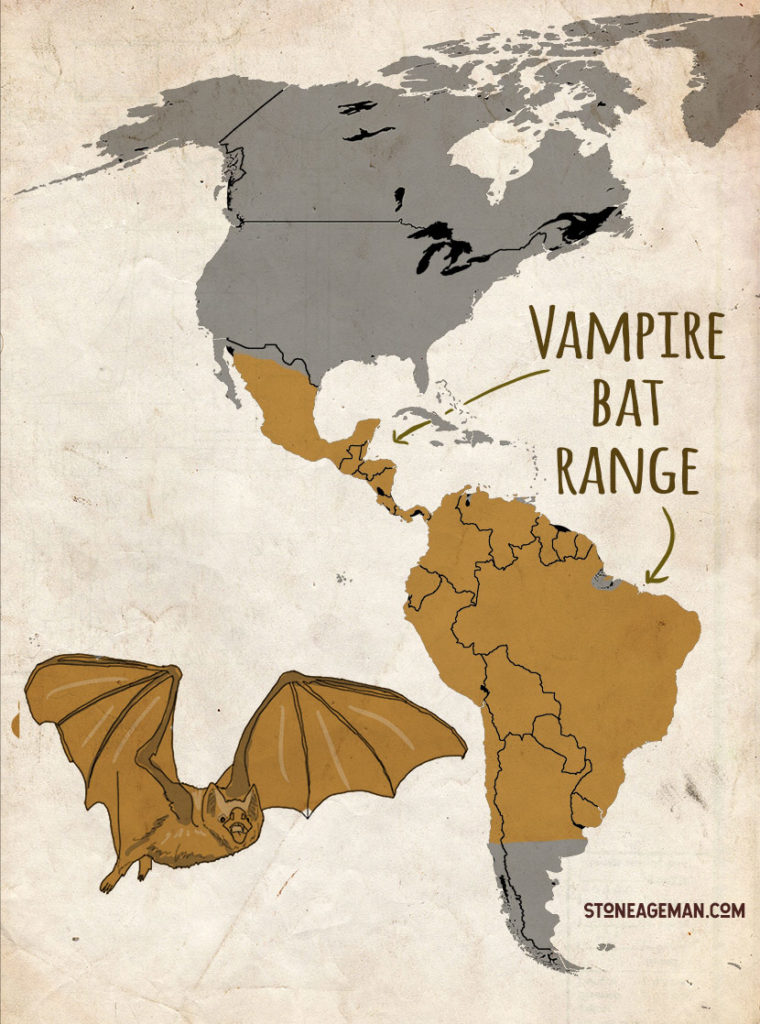

Vampire bats are the only bats in the world that drink blood! Don’t worry – they generally don’t prefer to drink human blood over other animals. But, like most animals, they are opportunistic when it comes to an available food source – so they can definitely drink your blood. In total, there are three species of vampire bats that are known to drink the blood of humans. Even though it is extremely rare and conditions would have to be just right for it to occur, part of the vampire myth surely came from bizarre events of bats feeding on humans.

Most of the time vampire bats get a meal from a larger herbivore like a goat, cow, sheep or a horse. They sneak up on their sleeping prey by crawling on the ground – it’s quieter that way. Once they get close, they use heat sensing organs in their nose to find where the veins and arteries are near the surface. They have sharp teeth to sheer away the hair that’s in the way. Then they make a small incision in the skin with their needle-like teeth.

Once the cut is made, they lick the wound. Their saliva is full of powerful anesthetics that dull the pain (so their prey doesn’t feel it), and blood thinners keep the blood flowing. In fact, this anticoagulant property in their saliva is super valuable to us. Doctors now use synthetically produced versions of these compounds to increase the flow of blood in stroke patients.

A vampire bat is so good at feeding unnoticed that it can feed up to 30 minutes at a time. And fortunately a bite here or there isn’t going to take enough blood to kill anyone. The real problem is that bats are the perfect transmitters of other diseases. In the case of the vampire bats, the concern is rabies.

Rabies

It’s estimated that about 0.5% of all bats carry rabies. That’s one in two hundred! While that may sound small, it’s high enough that you have to be very careful interacting with wild bats. Fortunately, bats with rabies rarely transmit to people as they’re often quite disoriented and have a hard time flying. That means you don’t have to worry about a rogue bat falling from the sky, biting you and giving you rabies. But it’s also why researchers who handle bats take careful precautions, like getting a rabies vaccine before doing field work. It’s also why you do not want to pick up or handle a bat on your own. The potential for disease transmission is just too high to take the risk.

Ebola

After the 1995 Hollywood film Outbreak, the deadly Ebola virus claimed its role in infamy on the world stage. There is some evidence that bats may actually be the original hosts of Ebola. Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) kills up to 90% of humans infected by it, and in spite of humanity’s efforts, there is no known cure. If you contract the virus without having gotten the newly developed vaccine, only supportive treatment can be offered.

Other viruses

Bats are currently known to carry 137 different viruses. Of those, we know of 61 viruses that can transfer to other species, such as humans (known as zoonotic viruses). They can carry nipah, marburg, sars, and various coronaviruses. Covid-19 most likely was carried by bats first, although at the publication of this book, we’re still unsure where that virus came from.

Part of what makes them great hosts for viruses is that bats love hanging out in groups. Most infected bats don’t die, so they can live long, healthy lives – all the while transferring viruses to other bats. Humans can be infected by many of these viruses through direct contact or (more commonly) through the ingestion of food or water that has been contaminated. An example of this might be a water source that is contaminated by bat feces (guano) – many animals could drink from that source. If those animals are consumed by humans, the virus can be contracted and begin to spread.

Histoplasmosis (Cave Disease)

The other big problem is that bat droppings are the perfect place for a fungus known as Histoplasma capsulatum to grow. Histoplasmosis is a lung disease caused by infection with this fungus. Symptoms are similar to pneumonia. You can definitely treat it, but untreated chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis has a death rate of up to 50%..

Even though our relationship is complicated, being scared of bats or getting rid of all of them is never the answer – not even close. Instead, possibly the best thing we can do is leave bats alone. They can’t transfer diseases to us if we don’t get ourselves in close contact with them and hold livestock raising practices to a high standard of safety.

Scenarios to Avoid with Bats

- Avoid going into dusty bat caves without proper masks and protection.

- Don’t handle a live bat if you don’t have training and especially if you don’t have a rabies shot and protective gloves. In many countries you need a licence or permit to handle bats. It’s both to limit disease spread and to keep the bats safe.

- Don’t eat bats. Bats are eaten in many places in the world, but the risk of direct transmission of a viral disease is too great a risk in the opinion of some medical experts. No bat-on-a-stick for me!

How to make living with bats better

- We should support making it illegal to farm or consume live bats to help limit the spread of these diseases. Yes, this is a thing.

- On a similar note, don’t support illegal markets that move living or dead bats around the country. There is currently no definitive evidence that links Covid-19 to bats, but we know there is potential transmission – so why risk it?

The Most Dangerous Bat

The closest thing to a dangerous bat is a rabid vampire bat or a bat full of viruses. In both cases, it’s really not the bat that’s dangerous, but what’s inside the bat. Again, the thing that really makes bats potentially harmful is that they happen to be great vectors for disease.

How to Avoid a Bat “Attack”?

Since the three vampire bat species are the only ones that may take a meal from a human, the key is to avoid the very specific circumstances that would allow this rare event to occur. The vampire bat’s main prey is cattle in central and south America, so I highly recommend not sleeping next to a cow or goat at night in the tropics. In fact, if you’re near a ranch, make sure you’re sleeping inside or with a mosquito net. This is just common sense to prevent an assortment of critters from biting you in this area of the world. Too easy!

Why I wrote this article

A few years ago, I got special access to look for a long lost artifact under the holy city of Jerusalem in an abandoned Byzantine church. While that’s a story in itself, the one thing we saw a lot of were bats. The entire area was dusty and bat guano (aka bat poop) was all over the ground. I’ve hosted many shows where we’re in close contact with bats in caves. They’re my least favorite part of the job, but not because of the bat. It’s because of the poop.

On this unfortunate expedition under Jerusalem, the producer of the show contracted histoplasmosis from that experience and had to have medical treatment after filming ended. But don’t worry, if treated early enough, it’s not a terrible disease. He was fully recovered in a few weeks. Thank goodness.

Prefer Listening?

If you’d rather listen to this article, I’ve recorded it here to make it as accessible as possible.