How to Survive a Venomous Snake Bite

Venomous Snake Basics

There are approximately 3,800 different species of snakes in the world. Out of those only 375 are venomous.

Yet, for most of us snakes evoke an almost primal fear. It feels at times like this fear is part of our very DNA. In Genesis, the devil (the personification of evil) is represented in the Garden of Eden as a serpent. In fact, it’s hard to come across historical accounts that make snakes out to be kind, loving, and generous. The fear of them is somewhat justified, too. They kill many more people every year than sharks do.

In fact, the world health organization estimates there are as many as 5 million snake bites a year – half of which cause envenomations. Of those, there are on average about 100,000 deaths a year from snake bites. Most of those are in regions where both hospitals and antivenom are not available.

Some have hypothesized that the great eyesight we have as humans (only surpassed by predatory hawks) and the fact that our eyes are direct in front of our faces, is an evolutionary adaptation to being able to spot snakes in the undergrowth. Surely having this ability would aid in keeping you alive. But are venomous snakes really out to get you?

No. They are not.

The evidence is simple. In spite of the high number of deaths a year from them, venomous snakes don’t attempt to eat the humans they envenomate. The toxicity of their venom is an adaptation to two things – Immobilizing the prey they eat and as a defense against predation.

The toxicity of their venom and danger to humans is absolutely not because they are out to get humans. Their venom is used to immobilize their prey. Some of the most toxic species have venom that acts quickly so that their prey can’t go far and can’t fight back before they are consumed. Sea snakes eat fish that could swim away, so their venom is one of the most toxic and fast-acting. Put simply, venomous snakes have venom that is well adapted to the prey they eat.

To put it another way, humans are thankfully not on the menu. However, this is of little comfort if someone gets a lethal dose of venom from a self-defensive snake bite. Venoms are chemically complex, highly variable and cause a huge range of deadly and often grotesque consequences in the body. Let’s take a look at the basics of their venom to get a broad view of what we’re dealing with.

The Main Types of Snake Venoms

Different people have a range of reactions to the various snake venoms, so it’s somewhat hard to pinpoint exactly what happens when someone gets bitten. However, there are five broad categories of venom toxins – hemotoxins, neurotoxins, myotoxins, cytotoxins,and cardiotoxins. Each causes quite different kinds of damage.

- Hemotoxins destroy red blood cells, cause organ degeneration and general tissue damage. Vipers and pit-vipers have this sort of venom.

- Myotoxins and cytotoxins cause severe tissue damage. If not treated right away, they can cause loss of limbs.

- Cardiotoxins, as the name implies, affects the heart. They may cause the heart to beat irregularly or stop, causing death. Cobra venom includes a cardiotoxin.

- Neurotoxins: Cobras, mambas, taipans, and coral snakes contain neurotoxins. These toxins are destructive to nerve tissue and in general are very dangerous because they can shut down your ability to control muscles, like your heart and diaphragm which keeps you breathing!

Is there an easy way to distinguish a venomous snake?

The short answer is no, but location can help. In the United States for instance, we mostly just have to distinguish between venomous vipers and non-venomous colubrids (the coral snake is the only exception as it is venomous and not a viper). Because of that people have been taught to look for head shape and pupil shape.

Head shape – Vipers generally have a very pronounced triangular shape. Of course, there are other snakes, like pythons, water snakes and other mimics with triangular shaped heads so make sure this isn’t your only diagnosis.

Pupils – Vipers are known for their cat-like elliptical pupils. They are elliptical and look very different to the round pupils of most snakes. Then again if you’re close enough to distinguish the pupil shape, you’re too close.

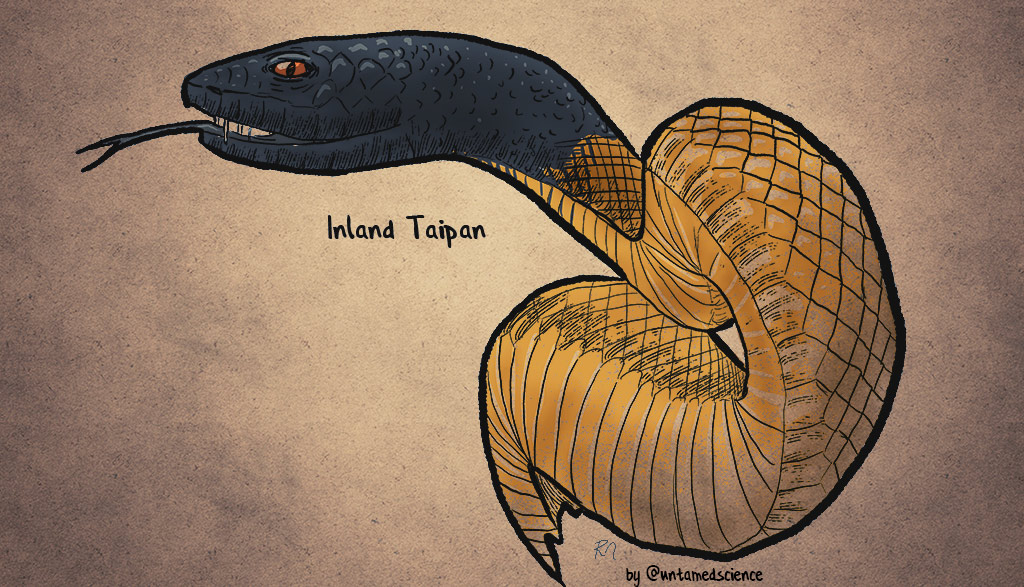

The real problem is that not all venomous snakes are vipers. In Australia for example, the most venomous snakes belong to a group of snakes called elapids. Cobras, mambas, king browns, and taipans belong to this family. They don’t have elliptical pupils or triangular head shapes. Sea snakes are elapids too and they’re extremely toxic. Finally, some colubrids are also venomous. All this to say it’s not extremely wise to trust general rules until you know a bit more about the snakes you’re dealing with in your area.

The best thing you can do if you live in areas with venomous snakes is to learn as much as you can about what you might encounter and avoid particular situations that might put you at greater risk of getting bit by venomous snakes.

Scenarios to Avoid with Venomous Snakes

There are definitely certain situations that put you in more risk of getting bitten by a snake. Here are a few.

- Don’t stick your hand into holes without knowing what’s inside. Snakes love to find homes in small crevices and will attack if they feel threatened.

- Avoid walking with your bare feet through thick brush without being able to see where you’re stepping. The simple solution to that is to wear some sort of boot with thick rubber or leather.

- Snake-proof your property. Ok, technically you can’t ever snake-proof your property but most people don’t want to have a venomous snake near their home, especially if you have young children or pets. A simple way to minimize your chances of an encounter is to keep mice and rodents at bay, which the snakes prey on. That might mean keeping chicken or bird feed in closed containers. It also means sealing the house properly with window screens and sealed doors. This will help make sure you can live in harmony with these creatures without fear of them entering the house.

- Don’t provoke the snakes. Many bites happen when people are trying to handle or kill a snake. While I understand the mentality, you should be aware that this may be the most dangerous moment. They can move quicker than you think!

- Don’t handle a dead snake. Believe it or not, many people are bitten by dead or decapitated snakes each year.

The Most Dangerous Venomous Snakes

A few years ago, I made a video titled “The most dangerous snakes in the world.” It got a lot of criticism because how someone determines the level of danger is a bit subjective. Is it the toxicity of the venom, the amount of venom they inject, fang length, how often they encounter humans, the general demeanor of the snake, or is it some scale combination of all these aspects? Truth be told the rankings don’t apply well to real life. You might even just say the most dangerous snake is the one that just bit you!

Let’s take a look at some of the most notable dangerous snakes and why they are in this category.

The inland taipan is arguably the most toxic, yet they almost never encounter humans in the wild. In fact, only keepers of captive inland taipans have ever been bitten.

Russell’s viper and saw-scaled vipers in Asia and India are responsible for more deaths and are very defensive and difficult to see due to excellent camouflage.

In the US the eastern diamondback is a massive snake that has the potential to inject tremendous amounts of venom.

The black mamba and the king cobra may be the two most feared snakes for a combination of defensiveness, size, and venom toxicity. Mambas in particular are known for being really fast.

How to Survive a Venomous Snake Bite?

If you’re bitten by what you think is a venomous snake, you can survive. Unfortunately, because snake venom varies tremendously, there are some variations as to best practices. Australian snakes for instance are often highly neurotoxic and hemotoxic and present unique challenges. However, all venomous snake bites require immediate action. So, here are some general steps you can take should you get bitten.

- Get safely away from the snake. Like in any first aid situation, your first task is to make sure you’re currently safe and won’t get bitten again. Then you can settle down to think.

- Stay calm and still. This may be the hardest part, but if you run and panic, the toxins will quickly travel through your blood to the rest of the body. You don’t want that. While you’re at it, remove your rings and bracelets.

- Make a plan to get medical attention immediately. Make a call – get a friend. Do what you need to get to the hospital, but make sure the plan isn’t driving yourself there. Remember, you may be intoxicated with a cocktail of potent venom! Many doctors use the term, “time is tissue,” when talking about envenomations. The quicker you get treatment the better chance you have of literally saving your own skin or life!

- Mark the bite. If you have a pen handy mark the bite and write the time it happened. As the redness expands from the bite, you can draw lines on your skin and add the time. This will help the doctors even if you fall unconscious.

- Know the local best practices: In Australia, wrapping and immobilizing the appendage could save your life. Same goes for coral snakes. That’s because a compression bandage you wrap on the arm or leg to prevent the spread of the toxin via your lymphatic system will help slow the effects. However, if you wrapped the appendage with most rattlesnake bites, it would increase the concentration of the venom, which damages local tissue. You don’t want that. That’s why it’s so important to know about the snakes near you and get to the hospital asap (and be ready for the biggest hospital bill of your worst nightmares).

What not to do with Venomous Snakes

- Don’t run or otherwise panic.

- Don’t drive yourself to the hospital. It’s likely you could lose consciousness and endanger others.

- Don’t cut yourself or attempt to suck out the blood.

- Don’t chase down the snake in an attempt to bring it to the hospital.

- Don’t wash the wound. This will interfere with the doctor trying to figure out what bit you.

- Don’t ice it. This won’t help and could damage the tissue.

- Don’t put on a tourniquet to your arm/leg. This could lead to even bigger problems.

The Take Home:

There is a reason we have an almost innate fear of snakes. However, that doesn’t mean we need to be paralyzed in fear because of them. In fact, if we only understand a bit about their ecology and behaviors, my hope is that it’ll turn into a lifetime of fascination with these magnificent, yet potentially deadly, creatures.

A Personal Note: Why I wrote this

I remember my brother’s first close encounter with copperheads vividly. Our family was sitting around a picnic table at night. One small yellow light lit the area. My Dad looked down and saw the copperhead and calmly said, “Don’t move, there’s a snake at your feet.” At this stage, I already had experience with snakes so I knew the best thing I could do was to not make a sudden move, especially with a venomous snake. My brother on the other hand couldn’t control his fear and jumped back with terror in his eyes. Luckily, this didn’t cause a strike.

At 12, his first experience with these snakes was fear. I always wondered why his response was different than mine. Some of his response seemed innate and some was probably learned from my mother’s response to snakes (she only likes dead snakes). Even I had some trepidation which I was trying to actively unlearn so that I could interact with these legless reptiles better.

I still stand by the fact that my response to the copperhead was the safest approach, but is that always the right approach? Let’s dive a bit deeper into these snakes so we can avoid and mitigate negative interactions that may cause harm, or a lifetime of fear.

Prefer to Listen to this?

If you’d like to listen to this short article about being safe with venomous snakes, I recorded it here to make it more accessible.