The Three-Age System: What it is and Why it Matters

The terms Stone, Bronze, and Iron Age are used frequently. What not everyone might realize, though, is that these labels refer to an actual “thing” called the Three-Age System. This was one of prehistoric archaeology’s first dating systems, and it revolutionized the field in the 19th Century.

Background

As with most breakthroughs, the Three-Age System was the culmination of several advancements in knowledge. For many centuries, the dominant understandings of prehistory in the West were based on the Bible. Hence, the world could only be 6,000 years old, and the art of metallurgy (smelting and shaping metals) had been around since humanity’s earliest days, because the Bible said so.

When Europeans found stone artifacts, they thought they were “ceraunia” that were created by lightning striking the ground. Late in the 17th Century, following contact with indigenous peoples in the Americas and South Pacific, European scholars began to realize that these ceraunia were crafted by people who did not know how to work metal. This led to much debate.

How could Europeans have learned metallurgy from Noah’s descendants – as the book of Genesis described – and then forgotten it? Gradually, antiquarians (early archaeologists), naturalists, and geologists began to acknowledge that both Earth and humanity were much older than they had imagined.

The stage was now set for a paradigm shift, which would be instigated by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1789 – 1865)

C.J. Thomsen

Thomsen took over as the secretary for Denmark’s Royal Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities in 1816. He was not an academic, but he kept up with scientific discussions and knew the Royal Commission’s collection of artifacts better than anyone. Thus, in 1819 he opened the Royal Museum of Nordic Antiquities.

Thomsen was forced to relocate his museum in 1832 to accommodate the large crowds it was attracting. This required him to reorganize the museum’s artifacts, and he chose to arrange them according to the chronological ages he had come to believe in.

According to Thomsen, first came stone tools and weapons, then bronze; and, finally, iron. He published this dating scheme in 1837 in an essay titled “Brief Outlook on Monuments and Antiquities from the Nordic Past.”

Thomsen was not the first person to propose a Stone, Bronze, Iron Age sequence for humanity’s past, but his proposal gained more traction than previous ones. This was partly due to timing, and the fact that Thomsen’s apprentice, J. J. Worsae, later uncovered empirical evidence to support Thomsen’s theory.

While it was not immediately accepted by everyone, Thomsen’s Three-Age System changed Western conceptualizations of prehistory forever. But what are the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages?

Stone Age

The Stone Age is the period of time before a society had widespread access to metal tools and weapons. Britannica says that the oldest human tools date to 3.3 million years ago, meaning the Stone Age may have begun before Homo sapiens existed.

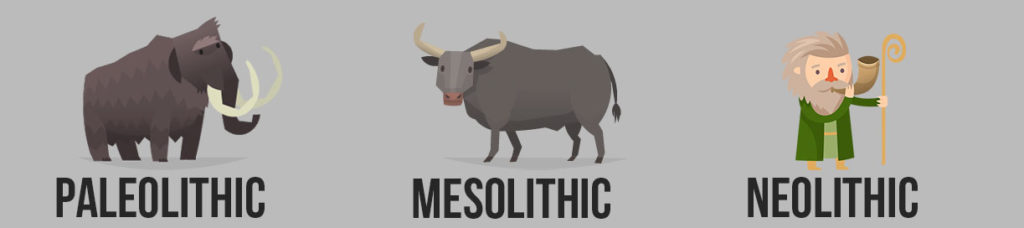

However, most sources claim that the Stone Age lasted from 250,000,000 BCE to around 3,000 BCE. It is often broken into the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic Periods, which describe increasing levels of technological and social complexity.

In the Paleolithic Period, which corresponds to the massive environmental fluctuations of the ice ages, everyone was hunter-gatherers. The Earth warmed as the Neolithic approached, which is the period when humans developed agriculture and animal domestication.

The usual story is that Middle Eastern societies first invented agriculture and animal domestication in 7,000 – 6,000 BCE, and then this knowledge spread throughout Eurasia (Europe and Asia). While this is likely true to some extent, archaeologists are finding evidence that farming sprang up independently in parts of Europe at around the same time, raising the possibility that multiple peoples may have learned to domesticate plants and animals at similar times.

The Mesolithic Period represents the transition between hunter-gatherer (Paleolithic) and agricultural (Neolithic) life.

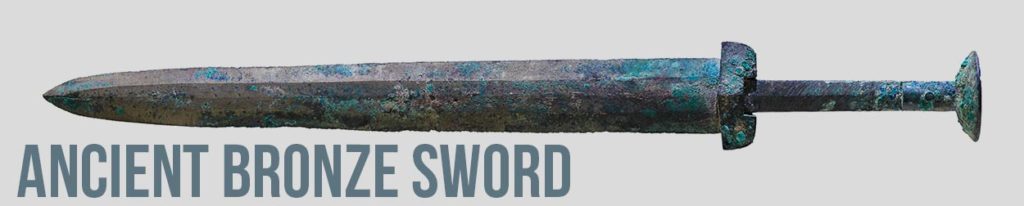

Bronze Age

A society entered the Bronze Age when it learned to produce and utilize bronze tools and weapons. This first began in about 3,300 BCE in the Middle Eastern civilization of Sumer.

Ancient peoples learned to make bronze by mixing copper – which on its own is not any better than stone – with small amounts of tin. This produced a hard metal that made excellent tools and weapons.

A great deal of cultural change also took place during the Bronze Age. This was the age during which humans invented the wheel and written language, when King Hammurabi developed an advanced legal system, when the Classic Greeks laid the foundations for modern democracy, and the glory days of Ancient Egypt.

Even larger changes began in 1,200 BCE, when people in the Middle East and Southeastern Europe learned to smelt iron.

Iron Age

Iron, while not tougher than Bronze on its own, is significantly more common than copper and tin. Hence, the invention of iron metallurgy led to the first mass-production of metal tools and weapons.

Nearly all of Eurasia had entered the Iron Age by 500 BCE, and most of the world is currently in this age.

Caveats

The Three-Age System contains important nuances.

First, the dates of the three ages are relative. Second, Thomsen created the Three-Age System to help him categorize Nordic artifacts; and, consequently, it most readily applies to Eurasia. Technological change did not occur at the same rate in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas, which were isolated by the Sahara Desert and the oceans, respectively.

The third nuance is that the Three-Age System is not a progressionist view of history: societies do not necessarily get “better” as they shift from one age to the next, they simply become more complex.

Wrapping it up

Despite the above caveats, the Three-Age System provides a convenient framework for quickly describing the evolution of human technologies and social systems. Since it focuses on tool-making materials, which archaeologists can empirically study, it is also fairly objective.

Today, however, we have ways to more precisely date prehistoric artifacts. Those techniques may be the topics of future articles here on StoneAgeMan. And, as a reminder, we have a StoneAge Man youtube channel.

References

Archaeology Soup. (2011). Aspects of Archaeology: The Three (and a bit) Age System.

Bronze Age. (2019). History.com.

Eskildsen, K. (2012). The Language of Objects: Christian Jürgensen Thomsen’s science of the past. Isis, 103(1), 24-53.

FerreroNutella. (2005). The three ages of human antiquity. Everything2.

Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K. (2007). The Three-Age System. Bad Archaeology.

Goodrum, M. R. (2002). The meaning of ceraunia: archaeology, natural history and the interpretation of prehistoric stone artefacts in the eighteenth century. BJHS, 35, 255-269.

Heizer, R. (1962). The background of Thomsen’s Three-Age System. Technology and Culture, 3(3), 259-266.

Hirst, K. K. (2019). Three-Age System – Categorizing European prehistory. ThoughtCo.

Høst-Madsen, L., & Harnow, H. (2012). “Historical archaeology and archaeological practice in Denmark.” In Across the North Sea, Later Historical Archaeology in Britain and Denmark, c. 1500-2000 AD.

Iron Age. (2019). Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Major Periods in World History. Biography Online.

Movius, H. L., Gimbutas, M., Braidwood, R. J., Pittioni, R., Adams, R. M., & Keesing, F. M. (2018). Stone Age. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Rowley-Conwy, P. (2004). The Three Age system in English: New translations of the founding documents. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 14(1), 4-15.The Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages. (2019). Essential Humanities.