Indian Pipes (Ghost Pipes ) : The Forest’s Pain Reliever That Are Risky But Effective

The ghost pipe (also known as the indian pipe) is white to almost translucent. We see it as it pops out of the forest as if it plant had a baby with a mushroom. It’s clearly a flower stalk yet is easily mistaken by the casual passerby as a mushroom. This rare find is actually a parasitic plant, that has incredible pain relieving medicinal properties. Don’t stop reading here though. This historically medicinal plant is not without risk and there are good reasons why it’s not commonly used today.

Biology 101 – Are Indian Pipes Parasites?

Yes. Indian pipes are considered parasites since don’t actually get their own energy from the sun. They’re what we call myco-heterotrophs, meaning they actually get their energy from fungi underground. Those fungi in turn get some of their energy from the plants around them. This is the main reason why it’s almost impossible to cultivate Indian pipes at scale. You’ll only find these in healthy forests that have had time to grow and form healthy relationships with fungi. And if you really want to get nerdy about it, recent research describes how they really only form relationships with mushrooms in the Russulaceae family.

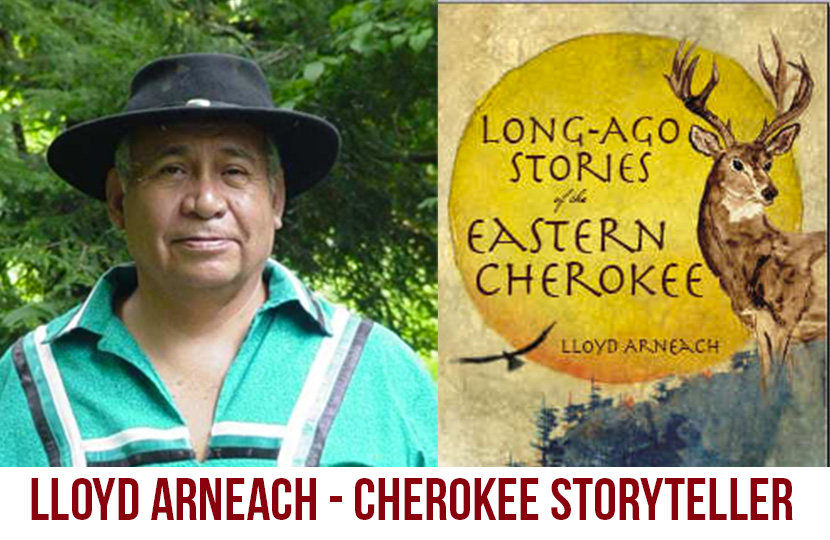

The Cherokee Legend of the Ghost Pipe

The Cherokee have a legend about the Indian pipe that was passed down orally from generation to generation. The legend tells the story of ancient chiefs who would meet to settle arguments and when they were done would smoke the peace pipe. One time they smoked the peace pipe before actually settling their arguments. They continued to argue for 7 days at which time the Great Spirit turned the chiefs into these translucent indian pipe flowers that now grow where relatives and friends had quarreled. Lloyd Arneach recounts it as follows.

Before selfishness came into the world, which was a long time ago, the Cherokee happily shared the same hunting and fishing lands with their neighbors. However, everything changed when selfishness arrived. The men began to quarrel with their neighbors.

The Cherokee began fighting with a tribe from the east and would not share the hunting area. The chiefs of the two tribes met in council to settle the quarrel. They smoked the tobacco pipe but continued to argue for seven days and seven nights.

The Great Spirit watched the people and was displeased by their behavior. They should have smoked the pipe after they made peace. The pipe is sacred and must be treated with respect. He looked down upon the old chiefs, with their heads bowed, and decided to send reminders to the people.

The Great Spirit transformed the chiefs into white-gray flowers that we now call “Indian Pipe.” The plant grows only four to ten inches tall and the small flowers droop towards the ground, like bowed heads. Indian Pipe grows wherever friends and relatives have quarreled.

Next the Great Spirit placed a ring of smoke over the mountains. The smoke rests on the mountains to this day and will last until the people of the world learn to live together in peace. That is how the Great Smoky Mountains came to be.

— Lloyd Arneach (Eastern Band of Cherokee)

American Indian Magazine

Winter 2010 “The Storyteller’s Art: Sharing Timeless Wisdom in Modern Times” by Anya Montiel

Pages 34-39

Can you Eat the Indian Pipe?

Yes and no. You can usually eat a small quantity of any plant. The upper threshold depends on the types of compounds in the plant. Indian pipe has a fair few compounds that are toxic in large doses.

It’s not recommended to eat many of them because of the presence of a number of alkaloids and glycosides that have been proven to have toxicity at fairly low consumptions. In researching it, I found that one flower alone wasn’t highly toxic so I did give one flower stem a try (as seen here).

Some people say Indian pipes taste a bit like asparagus when cooked. I never tasted that however I can vouch that if you eat it raw it’s almost tasteless. What they did have was a spicy aftertaste. I find this to be very beneficial for humans as it really doesn’t make you want to keep eating them. One is about all you can get down before the spice kicks in.

The reason you wouldn’t eat them has a lot to do with the glycosides in them. In particular they discovered grayanotoxin (formerly known in the literature as andromedotoxin, acetylandromedol, and rhodotoxin). These toxins are present in a large number of flowers, twigs, and leaves in the Ericaceae family (of which Indian pipes also belong). Grayanotoxins mess with the sodium channels of the neurons. For those that need a biology review, sodium channels are part of what controls nerve firing. Without nerves firing, you loose the ability to move the muscles in your diaphragm (among other things). Thus, this chemical can cause people to have respiratory depression and bradycardia. At high doses it also causes nausea, salivation, vomiting, weakness, dizziness and loss of balance.

These grayanotoxins can also be picked up from bees foraging on the flowers and get added to their honey. If people eat the honey that was derived from plants in this group there is the potential to get very sick (often called mad honey disease). This honey product is referred to commonly as “mad honey” (known as deli bal in Turkey). Even in quantities the size of a teaspon, this honey can bring on light headedness. In higher doses it can bring hallucinations. While mad honey is somewhat toxic, it’s also something that clearly alters your physical state and hence I can totally understand how using something with these grayanotoxins may have been very popular.

Are Indian Pipes Medicinal?

While we don’t generally use indian pipes in our modern pharmacopeia. That’s in part because our modern medicines revolve around isolating a particular compound, synthesizing it and adding it to a pill in known proportions. Any plant is going to contain many compounds. Let’s look at what exactly we know is in this plant and compare it to how it has been used traditionally.

Traditional Uses of the Indian Pipe

Traditionally there is documentation that it was used by American Indians for many ailments. A simple search of the Native American Ethnobotanical database pulls up the source records of reports of how it was used. The following is the summarized list.

The Cherokee used it is an anti-convulsive where they first ground up the roots and then gave during epilepsies and convulsions. They also crushed it up and rubbed on bunions or warts. The juice and water was used to wash sore eyes.

The Cree Indians used it as a toothache remedy whereby they chewed the flowers.

The Mohegan Indians used it as an analgesic, taking an infusion of the root or leaves for pain due to colds. Basically it was used to reduce the effects of fevers and pain.

The Thompson Indians on BC used a poultice of the plant for sores that would not heal. They also noted that an abundance of the plant in the woods indicated many mushrooms that season (which makes sense given the relationship it has with mushrooms).

The Potawatomi used it as a gynecological aid. An infusion of the root was taken for female troubles – how exactly, I could not find.

Modern Use of Ghost Pipes (Indian Pipes) by Herbalists

Modern herbalists sometimes use it as a nervine. Nervines are herbs and plants that can potentially help regulate the nervous system. Nervine tonics are a bit outside traditional pharmaceutical ways of thinking. The goal of nervine tonics is to to restore a depleted, stressed or anxious nervous system.

Herbalist, Seán Pádraig O’Donoghue, uses it in an interesting way. We discussed in this video:

Should I use the Ghost Pipe?

The ghost pipe isn’t for those new to herbal medicine. It has potentially toxic grayanotoxins that aren’t pleasant at high doses. However, they have been used by many for some pain relief. If you’re into plant medicines and have a way to collect some for a tincture (sustainably), then it might be a great plant to try one day. Just be careful and respectful of the forest.

Disclaimer: The StoneAgeMan blog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. We are not responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided. Always consult a healthcare professional before using plants for medicinal purposes.