How to Identify, Avoid, Treat and Survive Poison Ivy

Poison ivy doesn’t contain a toxin. Plus, it kills in a way that’s contrary to almost everything we know about toxins in plants.

To avoid having a terrible reaction you need to learn to identify poison ivy and also treat it should you accidentally touch it.

Poison Ivy Basics

It turns out that poison ivy is deadly because of an oil within the plant called urushiol. This oil isn’t a toxin. It’s a relatively harmless compound, except for the fact that most people’s bodies have an adverse reaction to it.

A good analogy here are allergies to tree pollen or house cats. Petting a cat is pretty harmless unless you happen to be allergic to cats. If you are allergic to the felines, your body overreacts to what it thinks is a threat – and you break out in rashes, itching and, in the worst case scenario, anaphylaxis (which can hinder your ability to breath and can send the body into shock).

Urushiol is somewhat similar in that it’s more of an allergen. The first time someone gets urushiol oil from poison ivy on their skin, they may not react at all. The body has never encountered the compound and doesn’t have antibodies to mount a decent defense. It may take a week or more for your body to produce enough antibodies for a rash or other reaction to occur. The initial response to the plants oils can be delayed, but when you have had enough exposure to build antibodies, you get a quicker reaction each time you’re exposed after that.

Classic reactions to poison ivy involve puss-filled red rashes that itch like crazy. Often it creates large blisters. Scratching them breaks the skin and oozing puss goes all over. One positive thing is that the oozing liquid is not toxic and it won’t spread anything. It’s just gross. If you’ve ever had this happen to you, you won’t soon forget.

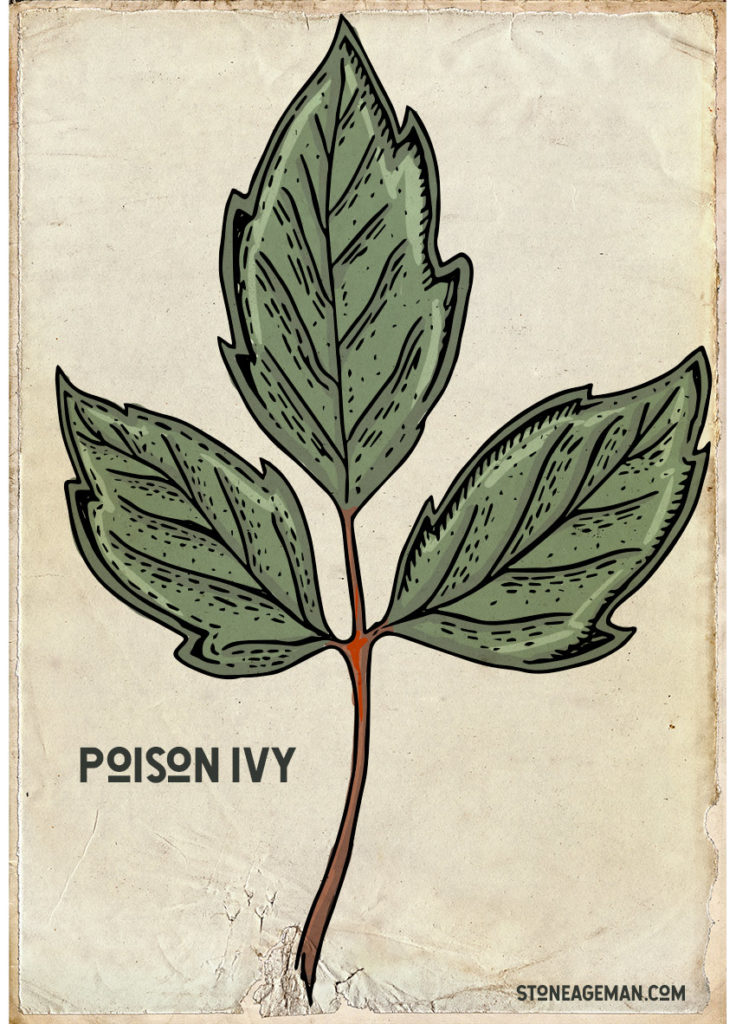

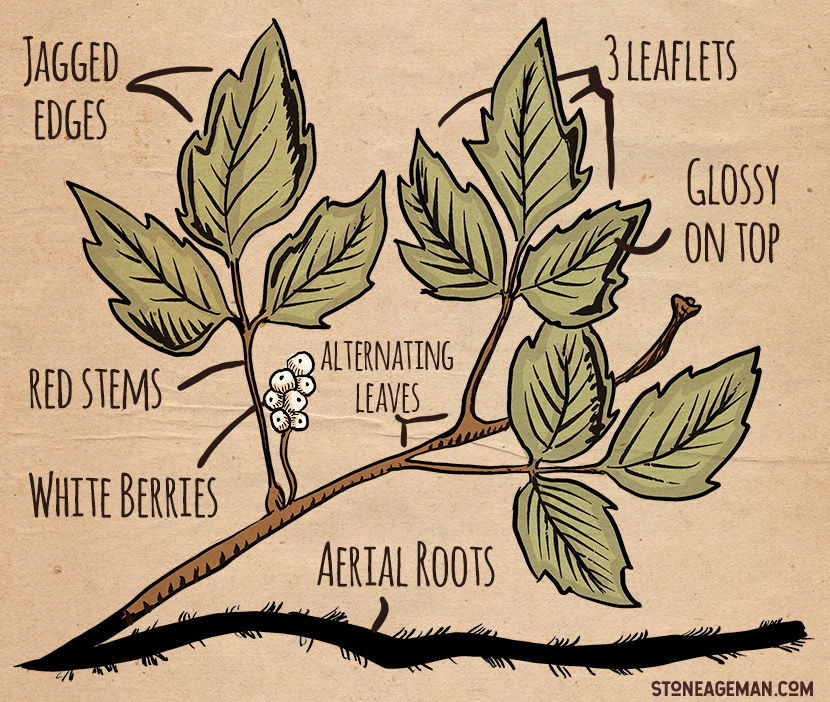

How to Identify Poison Ivy!

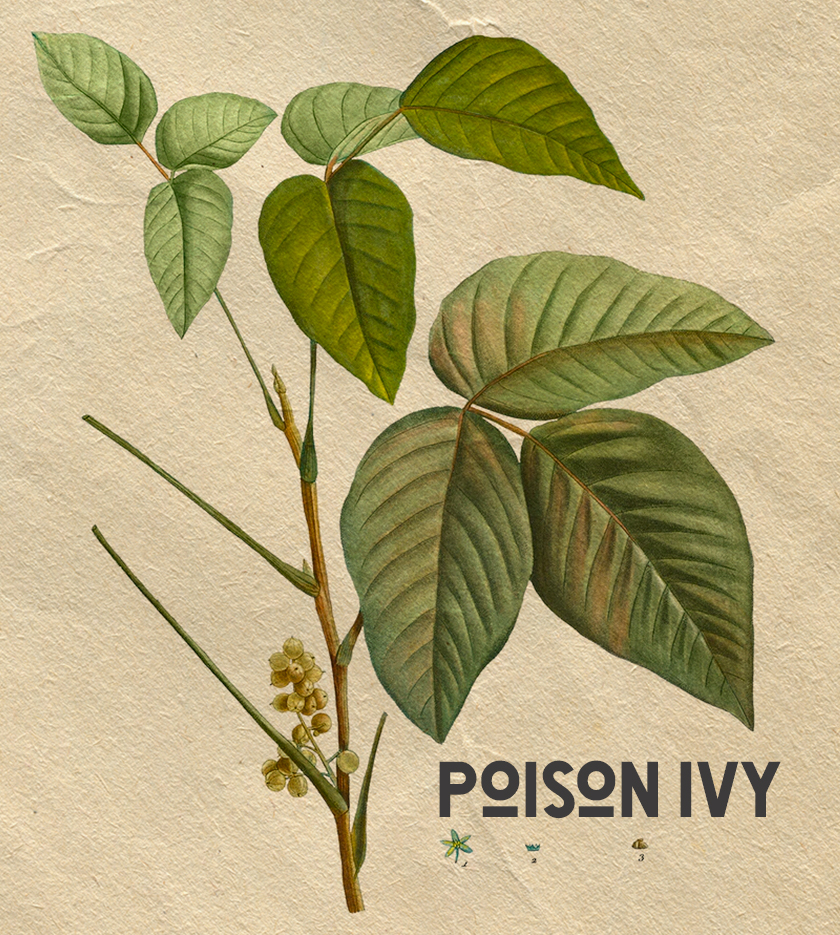

Identifying the plant is important. It’s your first defense. There are three easy-to-remember phrases that are often used to identify poison ivy.

- “Leaves of three, let it be.” Granted there are some other things in the forest with three leaves – like box elder, kudzu, and blackberries – but this phrase is a good start.

- “Hairy vine, no friend of mine” Many vines only have leaves far up in the canopy. That means, all you’d see is a vine attached to a tree. Yet, poison ivy has a very characteristic “hairy” vine. If you touched that hairy vine, you’d also get exposed to the dangerous oils.

- “Berries of white, danger in sight.” Many of the berries you’ll see in the forest are red, so a small white berry is at the very least, a caution to look out for poison ivy. Just realize that berries are only present for a small period of time on the plant.

If you’re still uncertain, you can (of course) do a quick internet search on your phone to make sure you’re correctly identifying poison ivy. Once you correctly identify it, it will become easy to spot! I have a fun, detailed video on this via StoneAgeMan on YouTube.

Scenarios to Avoid with Poison Ivy or Poison Oak

- Don’t burn poison ivy. The smoke will get into your lungs and coat them with the oils. It will also cover your clothes and skin with a fine layer of oil. This can be disastrous. I’ve seen the fallout from burning poison ivy firsthand when my best friend was covered in smoke from a nearby prescribed burn in the forest. His entire torso and legs were covered in pus-filled boils, and it took lots of medication and time to fully recover.

- Don’t eat the berries. Your throat, which you definitely need for breathing properly, could swell and react adversely.

- Be careful petting your dog in poison ivy country. Dogs rarely react to poison ivy, but the oil can stay on their fur and transfer it to anyone who touches them.

- Don’t skin a rabbit that’s been living in poison ivy and then wear the pelt on your body without first washing it thoroughly. Let’s just say I know someone who figured this out the hard way. Those oils are persistent and hard to get off.

The Most Dangerous Poison Ivy

The most dangerous poison ivy seems to be the kind you can’t see. In the winter, it is common to grab sticks and dead vines to burn in a campfire, some of which may actually be leafless poison ivy. Two of my colleagues have had severe, poison ivy reactions from inhaling smoke in this fashion. Both sent them to the emergency room because their whole body swelled up from the reaction.

How to Survive Poison Ivy Rashes and Get Better

The biggest key to surviving and preventing a reaction is being able to identify poison ivy and making sure you wash the oils away properly. I get exposed to a lot in the forests of the Carolinas, but properly washing up goes a long way to prevent a rash.

If you can already identify poison ivy, you’ll know when you were exposed. The next step is to wash within 2-8 hours of getting any part of this plant on your skin. In addition to washing your skin, wash anything that came into contact with the plants – boots, pants, shovels, gloves, etc. The oil will stay on these and cause reactions even a year later!

If, for some reason, you didn’t wash it off and you start reacting, know that it’ll be bad for a few days and then it may take a month or more to fully recover. Calamine lotion, cortisone and Benadryl are often what you’ll use as topical treatments to alleviate the symptoms.

Whatever you do, try not to scratch away at the rash and blisters. Doing so could cause bacteria to invade, causing a severe infection.

If it gets worse, a dermatologist may prescribe something stronger – like a steroid called Prednisone to reduce the inflammation and mask the painful symptoms. If you are having a severe reaction, a dermatologist is your new best friend.

Fun fact: Urushiol and related oils are found in other plants and can cause similar reactions. Plants like poison oak and poison sumac are very similar. Most people may know that. However, related plants in the Anacardeaceae family like cashews and mangos can cause reactions in susceptible people as well. My wife loves mangos. On our honeymoon, we sat in a mango grove and gorged ourselves silly with perfectly ripe fruits – juicy goodness dripping from our faces and hands. Unfortunately, that was also the day we found out she was allergic to mango skin – Haley’s face and neck broke out in a mask of red itchiness. We still love to eat mango – we just avoid the skin like it’s poison ivy now!

Prefer Listening?

If you’d rather listen to this article, I’ve recorded it here to make it as accessible as possible.